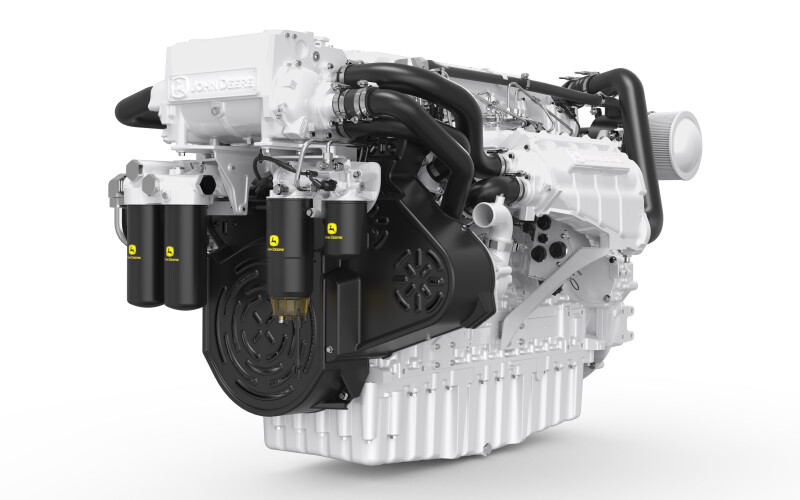

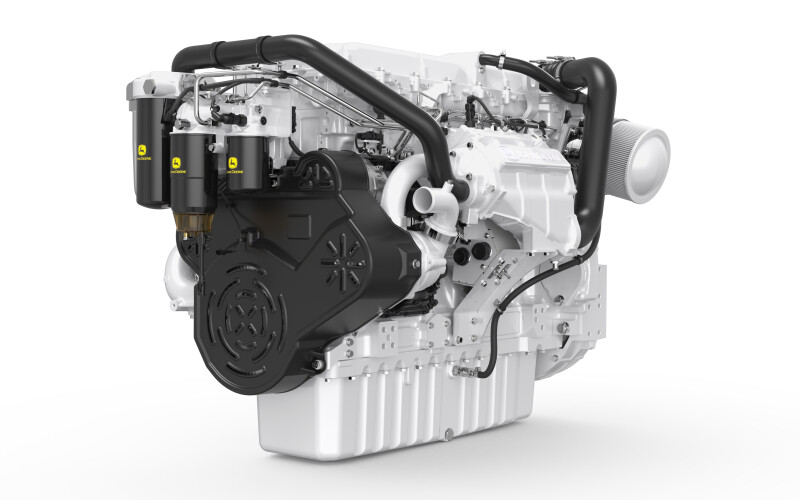

With its new JD14 and JD18 commercial marine diesels, John Deere has rolled out a pair of engines designed to be more durable, easier to service, and better connected to shoreside support teams. Production is slated to begin in 2026.

HEAVY-DUTY FOCUS

As it does with all its marine engines, John Deere marinized engines that were originally developed for agriculture applications to create the JD18 and JD14. For the first time, the company developed the engines side by side, creating commonality for some components and systems.

“We evaluated the pluses and minuses of developing these engines at the same time versus doing them separately,” said Vincent Rodomista, marine business and product manager at John Deere. “There’s a big demand for both of these engines, and both were pretty high priority for us.”

The numbers in the engine names indicate the displacement in liters. The JD14 differentiates itself from the 13.5L Powertech engine with a high-pressure common-rail fuel system. The older 13.5L engine has unit injection. “We have a lot more fl exibility in how we design the calibration on the software for the engine because we have pretty much infinite flexibility in fuel timing with a common-rail fuel system,” said Rodomista.

Common-rail injection lets John Deere optimize fuel effi ciency and reduce emissions while increasing the power on the JD14 to 803 hp compared with the 13.5L engine’s 750. With the power increase also comes an increased duty-cycle rating. The JD14 is rated at M4, while the 13.5L is M5.

Regarding the additional weight, Rodomista said, “We thought it was a fantastic tradeoff to get the additional power and a heavier duty cycle in a commercial engine.”

The JD18 has the highest duty rating at M1, which is basically an unrestricted load factor. “The lower the number, the more heavy-duty it’s suited for,” he added. “It can use that full power, the rated power, 24 hours a day, seven days a week.”

The M1 rating is for continuous, high-load marine propulsion, while M2 and M3 are for progressively less demanding applications with lower load factors and shorter periods of full power operation. These ratings help match engine capabilities to vessel usage, ensuring optimal performance and longevity, according to the manufacturer.

M4 and M5 ratings are for progressively lighter-duty marine applications with lower load factors and shorter durations of full power use. M4 is for general use, while M5 is for recreational and light commercial applications.

Intended exclusively to be used in inboard applications, the JD14 and JD18 have been engineered for target customers in the tugboat, passenger ferry, pilot boat, and fishing vessel sectors. Both engines have 50- and 60-cycle constant speed generator set ratings, too.

For larger-vessel applications, the new engines have a variable-speed auxiliary rating for driving cargo pumps on barges. These ratings also mean the engines are suitable for use as variable-speed gensets aboard vessels with diesel-electric hybrid systems that have energy storage with batteries.

EASIER TO SERVICE

To reduce maintenance costs and downtime, the oil change interval on the new engines is 500 hours, compared with 275 hours for the 13.5L.

The JD18 and JD14 also share the same seawater pump design. John Deere upgraded the impeller material from rubber to bronze for the JD18 and JD14. Instead of having to be serviced every 500 hours for a rubber unit, the time is extended to 10,000 hours.

The JD14 and JD18 each have a single turbocharger. For a cooling system, the JD14 has a single-circuit cooling system with seawater circulating through a heat exchanger while the coolant goes through an aftercooler prior to entering the engine block. On the JD18, the cooling system is a new configuration called XFM. This has independent cooling systems for the aftercooler and the water jacketing network, each with its own pump. “The heavy-duty commercial marine market’s clear preference is to not have seawater as the cooling medium in the aftercooler in order to reduce maintenance cost and downtime associated with changing zinc anodes, aftercooler fouling from growth or seaweed, and of course aftercooler failures due to corrosion,” said Rodomista.

The JD14 and JD18 are undergoing field testing in Europe and the U.S., said Rodomista, noting the engines will be put through their paces in tugboats, fishing vessels, ferries, and pilot boats as part of the trials. He said he knows who is getting the first production engines but could not disclose the company.

The same goes for pricing. The order board for the new engines is scheduled to open in November 2025, and that’s when pricing will be made public.

With more attention being paid to sustainability initiatives, John Deere designed the JD14 and JD18 to run on renewable diesel and hydrotreated vegetable oil fuels. Rodomista said the company is researching alternative fuels, but he did not have details.

The JD14 will compete with Volvo Penta’s D13, Scania’s 13-liter offering and MAN’s 12.6-liter engine.

Competitors for the JD18 will be the Caterpillar C18, the Cummins QSK19, and the 16-liter offerings from Scania and Volvo Penta.

DIGITALLY CONNECTED

With its new JD14 and JD18 diesels, John Deere has implemented its Connected Support technology that makes the engines more accessible for virtual diagnostics and has extended maintenance intervals, reducing downtime.

“We ship the engines with a modem and antenna that can connect wirelessly with a network on the vessel or with cellular towers when it’s in range,” said Rodomista

Dealers can now conduct remote diagnostics, determine what’s going on with the engine, and decide if a mechanic needs to visit the vessel to perform a repair. It also lets the repair facility be more efficient because it can prepare ahead of time, ordering parts for the job and getting the tools ready.

In addition, having each engine as its own network allows John Deere to constantly acquire data on it when a customer opts in. The company can compare that information with data on its servers for a given model or engine family. Rodomista calls it “predictive maintenance,” and explained, “We track and monitor any parameters that are becoming an outlier of normal operation. We can automatically provide the customer through our distributors and dealers with what we call predictive alerts, saying ‘Hey, something’s not right here. You better go check this.’”

John Deere provides the modem and antenna for no additional cost. “That’s a significant leap for us on the marine side that we can provide our customers. We pay for the cellular service,” he explained. “They don’t have to spend a dime as an ongoing concern for all these benefits and value.” A vessel or fleet owner can use the technology for remote monitoring and to share how an engine is performing in real time.

John Deere plans to apply Connected Support to its full marine engine lineup later this year.

If the vessel doesn’t have a satellite system and is out of cellular range, the system continues to collect the data. The next time it has a connection, it will do a data dump to John Deere servers.

Think about a crab-fishing boat in Alaska or swordfishing vessel out of Gloucester, Mass., heading out for days or weeks at a time. John Deere Connected Support can monitor the engine remotely and give guidance to the captain while the vessel continues to work.

“The ability for an operator to have remote support from a John Deere service provider through remote diagnostics is very important for our marine customers,” said Rodomista. “Currently, a customer would have to call a dealer and tell them about the systems and alarm codes and the technician does their best to troubleshoot. With remote diagnostics, the technician can actually run diagnostic tests on the engine remotely which is a huge leap in support capability.”